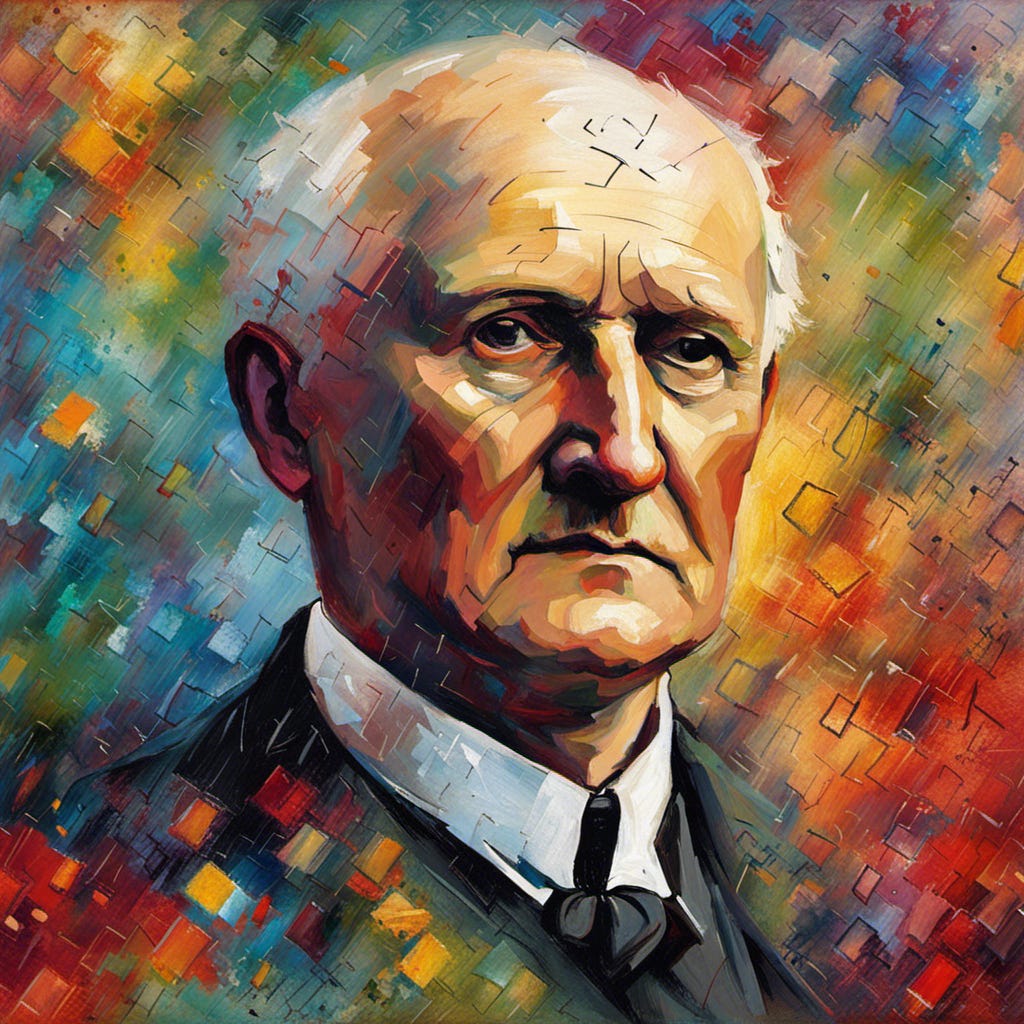

Anton Bruckner

have stopped trying to figure out why the music of one composer is popular and the works of scores of others are not performed but collect dust in the obscurity of music libraries. At the beginning of the 20th century, the American public did not care for Edward Grieg’s Piano Concerto in A minor, but today it is one of the most-performed piano concertos. Mahler’s music was not popular in the US until Leonard Bernstein popularized it in the 1960s. Neither Grieg’s nor Mahler’s music suddenly got better; public attitudes towards it changed.

Over the last few years I’ve been actively trying to stretch the boundaries of my musical knowledge by going deeper into the music of the composers I am already familiar with and also by more widely exploring new (previously unfamiliar to me) composers.

When I listen to music that is unfamiliar to me, at first it’s work. Yes, work. At first, I don’t understand that music and it brings me little pleasure – it’s just random, unconnected sounds. I may have to listen to a new piece half a dozen times before it clicks with me. I remember listening to Puccini’s La Boheme a dozen times, and at first I was baffled at how this opera could possibly be one of the most-performed operas. Today I don’t see how it could not be.

Sometimes, even after a dozen tries the music won’t click with me, and I put it into the “I don’t understand” pile. I try very hard not to use “I don’t like” when it comes to classical music, for two reasons. First, it implies that I am a judgment-worthy connoisseur (I am not!), and second, “I don’t like” has a finality to it, while “don’t understand” leaves the door for me to understand the music down the road.

I “understand” some composers quicker than others. Russian composers take the least number of tries – there must have been something in the water I drank as a child growing up in Russia. Mahler, Sibelius, and Bach, on the other hand, took a long time for me to understand. I still don’t understand all of Mahler’s work.

This brings me to the latest victim of my explorations, Austrian composer Anton Bruckner (1824-1896). As I’ve been listening to Bruckner’s symphonies and reading about him, I have found that Bruckner the person is as interesting as his music.

Bruckner’s ancestors were farmers. His father was a music teacher. Bruckner was a very diligent student and became a very talented organ player. Robert Greenberg writes:

The Church was Bruckner’s refuge and solace for the entirety of his life; he was as devout a man we will ever find outside a monastery or a foxhole. He believed completely that everything he did should honor God.

Bruckner was a total country bumpkin: naïve, simple, overly trusting, deferential and pious to a fault. (Bruckner followed to a “T” the Church’s proscription against sexual relations not sanctified by marriage.)

Bruckner searched for a bride all his life:

He was 43 when he fell in love with a 17-year-old, whose parents put a stop to the relationship. He fell for another 17-year-old in his mid-fifties. Though the parents in this instance gave the relationship their blessing, the young girl tired of Bruckner, and his passionate letters went unanswered. Later still he became infatuated with the 14-year-old daughter of his first love – that came to nothing and at 70 he proposed to a young chambermaid. Her refusal to convert to Catholicism ended that. Piety and pubescent girls are not an attractive combination. Bruckner died a virgin and was buried under the organ at St Florian (from Gramophone).

Bruckner must have had a rather unhappy life. I have a theory that the less happy the composer, the better, richer, and more emotional his music. Pain is an incredible stimulant of creativity. But what really fascinates me about Bruckner is that he started composing symphonies fairly late in his life.

Per Robert Greenberg:

… the “eureka!” moment he experienced in his 39th year, when in 1863 he heard a performance of Richard Wagner’s Tannhauser in Linz. Bruckner was doubly blown away: not just by Tannhauser, but by the realization that what made Tannhauser great was that it broke so many of the rules of harmony and counterpoint he had so assiduously studied!

From that moment, Bruckner embraced Wagner’s music with a mania that changed his life. Convinced that it was his mission in life to become the Wagner of the symphony hall, he composed a Symphony in C Minor in 1866.

Bruckner was writing his music for God. This is what he wrote to then-young Gustav Mahler:

Yes, my dear, now I have to work very hard so that at least [my] tenth Symphony will be finished. Otherwise, I will not pass before God, before whom I shall soon stand. He will say: ‘Why else have I given you talent, you son of a bitch, than you should sing My praise and glory? But you have accomplished much too little!’

Bruckner’s drive to please God must have kept him going, as success came to him seven symphonies and twenty years later, when he was 60. Just imagine this: twenty years of constant writing and rewriting six symphonies, six symphony premieres, six flops. He kept going. I admire that.

Today Bruckner’s music is not very popular. Critics say his symphonies are very long and somewhat slow and that they lack emotion and extended melodies. There is also a practical limitation: His symphonies require a much larger orchestra, and since they lack the recognition of Beethoven’s or Mozart’s, they are rarely performed.

I started listening to Bruckner with his Symphony Number 4 – it was his most-listened-to recording on Spotify. It is one hour and nine minutes long. If you run out of patience, do what I did. Don’t think of it as a novel, think of it as book with four independent stories (parts/movements). Listen to each movement separately many times, starting with the first one. I am listening to the first movement as I am writing this, and I can hear bits from various symphonies in this one – there is the grandeur of Saint-Saens third (“Organ”) symphony; I can hear parts of Berlioz’s Fantastique; and Wagner’s brass and violins are definitely in there. The beginning of part two has some of Mahler’s funeral-march-like sadness. And then you listen to the last five minutes of the symphony and it sounds like nobody else but a humble, very odd, sex-deprived, religious fanatic.

I am including several performances and implore you to sample them; they all sound different.

Vitaliy Katsenelson is the CEO at IMA, a value investing firm in Denver. He has written two books on investing, which were published by John Wiley & Sons and have been translated into eight languages. Soul in the Game: The Art of a Meaningful Life (Harriman House, 2022) is his first non-investing book. You can get unpublished bonus chapters by forwarding your purchase receipt to bonus@soulinthegame.net.

I'm curious to hear Bruckner's symphonies. Thank you for sharing!